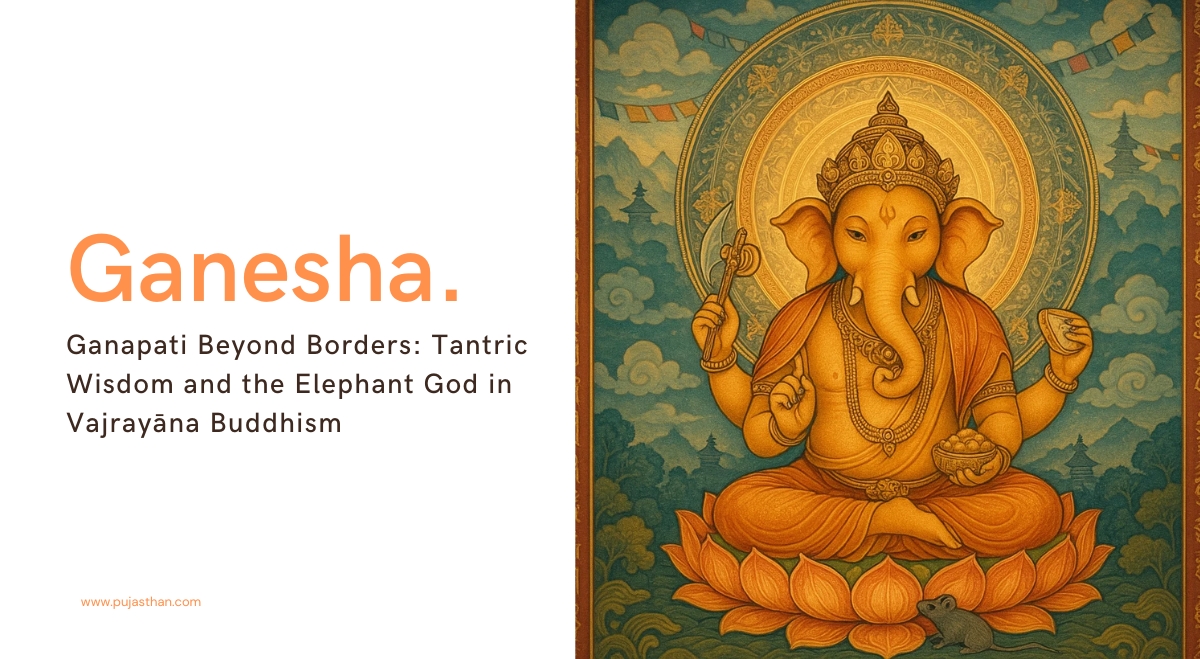

Imagine a quiet Himalayan monastery. The deep blue twilight bathes the stupa in mystery, while a lone monk lights a butter lamp before a small, ivory-colored statue. It has the unmistakable elephant head of Ganesha, adorned not with traditional Hindu garlands, but flanked by tantric offerings, mantras in Tibetan script etched around the base. What is Ganesha doing here?

Ganesha—known by names like Ganapati, Vināyaka, and Vighneshvara in Hinduism—is instantly recognizable in religious art around the world. What’s less known is his revered presence in certain Buddhist traditions, particularly within Vajrayāna Buddhism, which thrives in Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, and parts of Mongolia and Japan.

Far from being an outsider in these traditions, Ganapati is deeply embedded in some of the most esoteric Buddhist practices, embodying wisdom, success, and the clearing of inner and outer obstacles. His journey into the Buddhist pantheon is neither accidental nor superficial. It’s a tale of cultural synergy, spiritual inclusion, and doctrinal evolution.

This article explores how Ganesha, the elephant-headed remover of obstacles, entered the sacred halls of Buddhist tantra and became a unique figure in Mahayana and Vajrayāna practice. You’ll discover how he is portrayed, worshipped, and understood differently, yet reverently, in Buddhist contexts.

Whether you’re a seeker, a devotee, a practitioner of Dharma, or simply curious about how traditions interweave, this is your gateway into the tantric dimensions of Ganesha across thresholds.

Names of the Divine – Ganesha, Ganapati, Vināyaka in Buddhist Use

Linguistic Adaptations Across Cultures

Names carry energy. In Sanskrit, “Ganapati” means “Lord of Hosts” or “Leader of the Multitudes”—a title suggesting both command and community. In Buddhist contexts, especially Tibetan and East Asian, this name undergoes fascinating transformations while retaining spiritual potency.

In Tibetan Buddhism, Ganesha is often called Tsog Dag (ཚོགས་བདག་), literally “Lord of Offerings” or “Master of Assemblies,” reflecting the term “Ganapati.” In Japanese Esoteric Buddhism (Shingon), he’s known as Kangiten (歓喜天), meaning “Deva of Bliss,” often worshipped in dual form as male and female Ganapatis in tantric union—an imagery absent in Hinduism.

Each linguistic evolution reflects not just pronunciation shifts but theological re-interpretations. Where Hindu Ganapati leads the ganas (divine attendants), the Buddhist Ganapati may preside over offerings, tantras, or initiatory rites.

These naming conventions signal a deeper truth: while symbols and language shift, the core archetype of obstacle-clearing, auspiciousness, and transcendental power remain remarkably intact.

Ganapati as Obstacle-Remover in Mahāyāna

Even before entering the fully tantric Vajrayāna fold, Ganapati was already referenced in Mahāyāna texts as a protector deity. He appears on temple lintels, engraved beside Avalokiteśvara and Manjushri, his gentle elephant face signaling blessings to pilgrims and monks.

In some sūtras, Ganapati is invoked for protection, success in dharmic study, and ease in practice. His association with beginnings makes him a guardian not just of rituals but of spiritual initiation itself.

Unlike in mainstream Hindu worship, where Ganapati is often a household deity associated with material well-being, in Mahāyāna Buddhism, he evolves into a Dharmapāla (protector of Dharma), aiding practitioners in both mundane success and supramundane realization.

A Brief History of Syncretism – How Ganesha Entered the Buddhist Pantheon

Early Integration in Indian Esoteric Schools

The Indian religious landscape from the 6th to 9th centuries CE was a crucible of transformation. Buddhist tantra, Shaiva tantra, and early Shakta worship were co-evolving, and their practitioners often moved fluidly between traditions.

Ganesha’s image began appearing in Buddhist tantric texts and mandalas, particularly those from Nalanda and Vikramashila universities. Here, he wasn’t merely “adopted” from Hinduism. Instead, he was recontextualized as a symbol of perfection, esoteric wisdom, and tantric guardianship.

His attributes—elephant head, broken tusk, large belly—took on deeper meanings: the wisdom to see beyond duality, the ability to digest complex teachings, and the power to trample ignorance.

In some traditions, Vināyaka was also seen as an inner obstruction—the ego—which had to be transformed into a guardian deity through mantra and ritual. This dual portrayal (enemy-turned-ally) is unique to tantric thought and forms the conceptual bridge between Shaiva and Buddhist Ganesha.

Tibetan Embrace and Vajrayāna Systematization

By the time Vajrayāna was systematized in Tibet (8th–10th century CE), Ganapati was a fully integrated figure. Tibetan texts describe Heruka Ganapati, a wrathful form surrounded by flames, trampling over obstacles both literal and symbolic.

These forms are not just decorative—they’re ritual entities, invoked in initiations, protector practices, and tantric sādhanās. Lineages such as the Nyingma and Kagyu schools maintained secret visualizations and chants dedicated to Ganapati, aligning his energy with that of Vajrapāṇi and other protectors.

In this form, Ganesha becomes not a “borrowed god,” but a symbol of enlightened power, wielded by adepts for the benefit of all beings.

Forms of Buddhist Ganapati – From Heruka to Siddhi Vināyaka

Heruka Ganapati – The Fierce Protector

In the vivid and sometimes terrifying pantheon of Tibetan Buddhism, wrathful deities serve a sacred role: they destroy ignorance, fear, and spiritual stagnation. Heruka Ganapati is one such deity—an intense, ferocious version of Ganesha, depicted with flaming hair, multiple arms-wielding weapons, and a dynamic posture crushing demons beneath his feet.

Far from being evil or malevolent, Heruka Ganapati is an enlightened being—an emanation of compassion so intense it takes the form of wrath. In the Vajrayāna worldview, wrath is not the opposite of love; it is love in armor, ready to clear the most stubborn inner obstacles. This form of Ganapati is not invoked casually. He is approached through ritual initiation, deep sādhanā (spiritual practice), and strict ethical preparation.

Iconographically, Heruka Ganapati may carry a vajra (symbolizing indestructible truth), a skull-cup (signifying the transformation of death into wisdom), and a noose (representing control over the monkey-mind). His elephant face remains constant, yet it wears an expression of unwavering focus and divine intensity.

Practitioners call upon Heruka Ganapati to guard their spiritual path, destroy inner negativity, and provide the energetic fire needed to break through samsāric inertia. His mantra practices are often kept secret, passed down within tightly held lineages. In some texts, he is aligned with Vajrapāṇi, the thunderbolt-bearing protector, amplifying his role as both a guardian and a purifier.

This fierce form might shock those used to the cheerful, round-bellied Ganesh of festival processions. But in the tantric path, wrath and love are two sides of the same divine coin. Heruka Ganapati reminds us that sometimes, to truly grow, we must be shaken awake.

Siddhi Ganapati – The Auspicious Bestower

At the other end of the spectrum is Siddhi Ganapati, a peaceful and graceful form of Ganapati who grants siddhis, or spiritual attainments. Unlike Heruka Ganapati, who clears obstacles through divine fire, Siddhi Ganapati smooths the path with gentle guidance, inner clarity, and meditative blessings.

He is often portrayed with soft features, sitting in padmāsana (lotus posture), holding symbols of abundance and spiritual maturity—such as a lotus, a bowl of sweets, or even a scriptural text. Siddhi Ganapati is particularly revered in tantric circles that emphasize devotional surrender and subtle-body practices, where his grace is invoked at the beginning of rituals to ensure mental stability, clarity, and inner auspiciousness.

Tibetan sādhanā manuals sometimes recommend visualizing Siddhi Ganapati in a golden hue, radiating light from his heart that dissolves all karmic blocks. His mantra is simpler and more melodic than the fierce invocations of Heruka. It’s designed not to shock the psyche into awakening, but to gently uplift and center it.

For lay practitioners or those without initiation, meditating on Siddhi Ganapati is a beautiful way to merge the devotional heart with meditative insight. He’s the ideal companion for students, seekers, and those stepping into spiritual disciplines, offering silent blessings from the threshold of every sacred endeavor.

East Asian Representations – The Twin Ganapatis of Japan

In Japan, Ganesha takes on a truly unique form known as Kangiten (歓喜天), literally “Deity of Bliss.” Rooted in Shingon Buddhism, Kangiten is worshipped in dual form—a male and female Ganapati embracing in tantric union. This imagery reflects perfect bliss born of non-duality, a core tantric ideal.

The iconography of Kangiten is often secret, kept hidden in inner sanctums of temples. Worship is intimate, involving offerings of sweets, rice, wine, and incense, and conducted with great reverence. Despite the unusual imagery, Kangiten is considered a bestower of material prosperity and spiritual harmony.

In modern times, businessmen and artists in Japan may quietly pray to Kangiten for success and inspiration, reflecting an ongoing cultural relevance that has moved beyond monastic walls.

The East Asian adaptation of Ganesha illustrates how the spirit of a deity transcends cultural boundaries, finding new expression without losing its essence. Whether Ganapati, Tsog Dag, or Kangiten, the elephant-headed deity continues to walk the sacred lands of Buddhism, blessing practitioners with both worldly joy and spiritual awakening.

Buddhist Sādhanās and Rituals Involving Ganapati

Primary Tantric Texts and Practices

Within the Vajrayāna tradition, the practice of sādhanā—structured spiritual disciplines involving mantra, visualization, mudrā, and offerings—is central. Ganesha’s presence in these practices isn’t just decorative or symbolic. In many traditions, especially those descending from the Nyingma and Kagyu schools, Ganapati is a key guardian figure in the early stages of meditation and tantra.

Texts like the Guhyasamāja Tantra, Hevajra Tantra, and Chakrasamvara Tantra include references to Vināyaka or Ganapati, sometimes in coded language, where he serves as a liminal gatekeeper. He is invoked to remove spiritual “obstacles”—doubt, distraction, laziness, and karmic weight—that prevent the practitioner from progressing through higher realizations.

These texts instruct practitioners to visualize Ganapati vividly: seated on a moon-disc, surrounded by fire or golden aura, holding implements like the axe (to cut attachment), the rope (to bind the mind), and the sweet modaka (representing the rewards of discipline). Some systems require transmission and empowerment to engage in this visualization fully.

Ganapati is especially revered in the “outer preliminary practices” (ngöndro), which set the stage for advanced meditation. Here, his role mirrors that in Hindu traditions—but through a tantric, meditative lens rather than a puja-centric framework.

Common Devotional Practices

While some forms of Ganapati worship in Buddhism are esoteric, there are accessible methods for lay practitioners as well. In Tibetan homes, Ganapati is often honored through:

- Lamp offerings (butter lamps placed before his image)

- Simple mantras chanted for protection and focus

- Torma offerings (ritual cakes) representing obstacles dissolved

- Mental prostrations and visualizations before major retreats

In Nepal, Newar Buddhists sometimes include Ganapati in family shrines, blending Tantric Buddhism and Hindu Shaivism in unique ways. This devotional Ganesha is less formalized and more intuitive—an embodiment of grace at the family altar, bridging religious identities through shared reverence.

Ganesha Mantras in Buddhism – Sounds That Bridge Traditions

Heruka Ganapati Mantra

Mantra is the heart of tantra. In Buddhist systems, Ganesha’s mantras are recited not just to praise, but to evoke specific transformational energies. The Heruka Ganapati mantra, though rarely published, often contains the seed syllable “GAM” or “GUNG”, embedded within a matrix of sacred sounds tailored to wrathful awakening.

Examples (adapted for accessible context, not exact lineage use):

“Om Gung Ganapati Heruka Hum Phat”

Each syllable activates a layer of the subtle body: “Om” opens the crown, “Gung” stirs the wisdom-mind, “Phat” cuts through illusion. These mantras are ideally received from a lama and practiced under guidance, as they open powerful psychic and karmic fields.

How They Differ from Hindu Mantras

Where Hindu Ganesha mantras are often melodic and inviting (e.g., “Om Gam Ganapataye Namaha”), Buddhist versions can be more rhythmic, fierce, and multi-syllabic, echoing their tantric focus on transformation over appeasement.

Their aim isn’t to “ask” Ganapati for help, but to merge with his enlightened qualities through mantra. It’s not prayer as petition, but mantra as transformation. Even when peaceful in form (like Siddhi Ganapati), the Buddhist mantra practices are grounded in the non-dual framework of Mahāyāna tantra—where the deity and the practitioner ultimately dissolve into oneness.

The Mouse, the Broken Tusk, the Sweet Modak

In both Hindu and Buddhist traditions, symbols serve as visual metaphors—layers of meaning packed into form. Ganesha’s most recognizable emblems include his mouse mount, his broken tusk, and the sweet modak he holds. While these appear in Buddhist representations as well, their interpretive lens subtly shifts.

In Hindu theology, the mouse (mūṣika) symbolizes desire or the ego—small, quick, and capable of gnawing through foundations. By riding the mouse, Ganesha is said to control the human urge for unchecked indulgence. In Buddhist tantra, however, the mouse takes on a deeper psychological tone: it represents the subtle undercurrents of the unconscious mind. When Ganapati is shown seated on or beside the mouse, it suggests mastery over the hidden, habitual patterns of karma.

The broken tusk, which Hindu tales associate with sacrifice and wisdom (as in the Mahābhārata story where he broke it to write the epic), also has a tantric echo. In Vajrayāna, it signifies the tearing away of duality. The tusk may also be interpreted as cutting through the two extremes of nihilism and eternalism—a central concern in Buddhist philosophy.

As for the modak, the sweet dumpling that Ganesha adores, Buddhist texts view it not merely as a treat, but as a symbol of the rewards of inner discipline. Some tantras even describe it as the “nectar of bliss” (ānanda), experienced at the culmination of inner union practices. It reflects the inner joy born of emptiness realization—a distinctly Buddhist layer added to a Hindu favorite.

These shared motifs highlight an important truth: the outer symbols remain stable across traditions, but their inner meanings evolve, shaped by each religion’s philosophical core.

Role in Initiation vs. Pūjā

In Hinduism, Ganapati is central to pūjā rituals, especially at the beginning of any new venture. A clay image, mantras, flowers, and offerings—this is the standard mode of invoking the elephant-headed god. But in Buddhist tantra, Ganapati often functions as a guardian deity during initiation (abhisheka).

When a disciple receives a tantric initiation into higher practices like Chakrasamvara, Vajrayogini, or Hevajra, Ganesha (or Vināyaka) may appear at the threshold of the mandala. He is meditated upon, visualized, and sometimes ritually “converted” from a Vināyaka (obstructive demon) into a protector deity through mantra and mudrā.

This is not a contradiction—it’s an alchemical shift. In tantra, what hinders becomes what heals. The ego, when properly understood, becomes the gateway to non-duality. Ganesha’s role in initiation, therefore, is as a threshold deity—one who both blocks and blesses, depending on your spiritual state.

In this light, the Buddhist Ganapati isn’t merely a recycled icon. He’s an evolving archetype, shaped by the spiritual needs of tantric adepts, yet rooted in a deeper metaphysical unity that spans traditions.

Theological Reflections – What Does This Syncretism Teach Us?

The story of Ganesha’s journey into Buddhism isn’t just a tale of cultural borrowing. It reveals something profound about both traditions: their capacity to absorb, transform, and reframe wisdom across doctrinal lines without losing reverence.

From the Buddhist perspective, Ganapati’s presence shows how skillful means (upāya) can take many forms. Whether it’s Avalokiteśvara with a thousand arms or Ganesha with a round belly and elephant head, the forms matter less than the realization they point toward.

For Hindus, this syncretism illustrates the expansive nature of dharma. Ganesha is not “owned” by any one sect; he’s a universal archetype—a remover of obstacles, a gatekeeper of sacred knowledge, and a beacon of inner transformation.

Theologically, Ganesha in Buddhism blurs the artificial lines we often draw between faiths. He reminds us that spiritual truth wears many masks—sometimes gentle, sometimes fierce, sometimes joyfully chewing on a modak.

More importantly, this integration encourages humility and curiosity. Rather than dismissing differences, we are invited to explore them. Rather than fearing syncretism, we’re challenged to engage it with discernment, respect, and depth.

The elephant-headed deity, across traditions, becomes a symbol of unity in diversity—reminding us that the goal of all paths, whether Vedic, Buddhist, or otherwise, is ultimately awakening.

Common Misunderstandings and Clarifications

“Buddhists don’t worship gods.”

While early Buddhist teachings emphasize non-theism, Vajrayāna developed a rich pantheon of deities, not as ends in themselves, but as reflections of awakened mind. Ganapati, like Tara or Vajrapāṇi, is an archetypal force—a bridge between the mundane and the awakened.

“Is Buddhist Ganapati just rebranded Hinduism?”

No. Though rooted in shared culture, the Buddhist Ganapati is ritually, symbolically, and doctrinally distinct. His role, mantra, and even iconography reflect tantric Buddhist priorities like non-duality, karma purification, and sādhanā-based realization.

“Can you mix mantras?”

Spiritual syncretism requires depth, not casual mixing. Many mantras are tied to specific initiations (abhisheka) and lineages. It’s essential to practice with guidance and intention, not as spiritual tourism. That said, uninitiated devotional practices to Ganapati—such as lighting a lamp, chanting peaceful mantras, or reflecting on his qualities—can still be meaningful, provided they’re done with respect.

“Isn’t Ganesha only Indian?”

While Indian in origin, Ganesha’s presence in Tibet, Nepal, Japan, and even Mongolia proves that spiritual archetypes are not confined by geography. His journey across Asia reflects a shared human need for protection, clarity, and beginnings.

Conclusion – Ganesha Across Thresholds

Across monasteries and mandalas, from Himalayan caves to Japanese temples, Ganapati’s elephantine form endures—not just in stone, but in spirit. He stands at the threshold of traditions, smiling with wisdom, holding the broken tusk of sacrifice, offering sweet blessings to all who seek.

His presence in Buddhism is not an anomaly. It is a testament to the porousness of sacred wisdom, to the way truth echoes through varied languages and forms. In Vajrayāna, he is not simply worshipped but transformed, from obstacle to opportunity, from form to realization.

Ganesha, whether you call him Ganapati, Tsog Dag, or Kangiten, continues to teach one core lesson: every beginning is sacred, every obstacle a disguised ally, and every path—when walked with devotion—leads home.

FAQs

1. What Buddhist texts mention Ganapati?

Tantric texts like the Hevajra Tantra, Guhyasamāja, and Tibetan sādhanās reference Ganapati, especially in roles of protector or guardian.

2. Can Buddhists chant Hindu Ganesha mantras?

Yes, especially peaceful forms like “Om Gam Ganapataye Namaha,” but deeper tantric mantras should be practiced with initiation.

3. Is Kangiten the same as Ganesha?

Kangiten is the Japanese Buddhist form of Ganesha, often worshipped in dual form representing bliss and non-duality.

4. What is the Buddhist view of Ganapati’s iconography?

It varies—wrathful, peaceful, and dual forms all exist. Symbolism reflects Buddhist themes of emptiness, transformation, and realization.

5. Why is Ganapati invoked before Vajrayāna rituals?

As a remover of obstacles, he prepares the practitioner’s mind and space for deep, transformative meditation.